China’s Economic Puzzle

We’re all accustomed to thinking of China as the fastest-growing economy in the world, but recent events have had global investors rethinking that story. At the start of the year, the Chinese stock market fell to five-year lows, and the economy is in the middle of a scary bout of deflation. Chinese stocks are selling at an aggregate PE of 7, compared with 22.2 for the U.S. S&P 500. Consumer prices are down roughly 1% from last year and deflation is predicted for this year as well.

At the same time, home prices have declined at an 8.5% rate, and a series of defaults from over-leveraged developers has triggered a collapse in commercial properties. This is significant since so much of Chinese wealth is tied up in real estate.

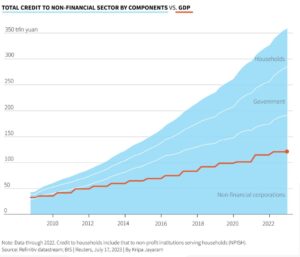

In the past, the Chinese government has propped up economic growth with stimulus spending on infrastructure, to the point where the country now has super-fast train systems with excess capacity and gleaming skyscrapers sitting empty. The Chinese central bank recently cut interest rates by 100 basis points, hoping that would trigger more borrowing and spending, but total debt of 350 trillion yuan—three times the country’s gross domestic product—makes you wonder how much more debt the nation’s citizens, companies and government would be willing to take on.

The recipe for escaping a recession or even a depression is relatively clear: clean up the property sector, restructure municipal and developer-related debt and switch to an economic model that doesn’t rely on ever-increasing amounts of debt-fueled stimulus spending. But nobody seems to expect the Chinese leadership to take drastic or even ambitious measures in those directions. Their goal, as one analyst put it, is to ‘maintain social stability,’ which can be translated to mean: staying in power regardless of the economic consequences.

Leftover Rollover

Suppose you’ve been contributing to a 529 college savings plan, but your son or daughter doesn’t use all the money for tuition, books etc. Do you just ask for the remainder of your money back?

Any contribution to a 529 plan is deemed to be a completed gift to the beneficiary—typically a child or grandchild of the donor. If you don’t want to incur a gift tax, then you can contribute up to $18,000 a year, but you can actually make five years of contributions at once—$90,000—if you treat the contribution as if it was spread over a five-year period. (You would do this on IRS Form 709 for all five years). If you only want to contribute, say, $50,000, then you can apply $10,000 per year. After the contribution, the money grows tax-free and can be used to pay college expenses without being taxed.

But back to the first question; you have the money in the account, but now it looks like the son or daughter isn’t going to use all of it. What do you do? You can indeed revoke the funds in the account, but that means they will be added back to your taxable estate, earnings will be taxable and the IRS will assess a 10% tax penalty.

You can roll the money from one 529 plan to another one, tax-free, so that it covers another daughter or granddaughter. That allows you to jump-start another child’s or grandchild’s college savings.

Finally, starting this year, you can transfer the stranded funds to a Roth IRA. There are restrictions. One of the most severe is that the 529 plan must have been maintained for at least 15 years, and the amount transferred must come from contributions and earnings made at least five years before the transfer. The Roth IRA must have the same beneficiary as the 529 plan, meaning that the money can’t go back to an account held by the parents, grandparents or other children. However, the owner of a 529 plan can change the beneficiary to another individual before the transfer.

In 2024, the aggregate amount transferred from the 529 plan to a Roth IRA for any individual cannot exceed $35,000. That means the transfer might not be a good option for parents whose child suddenly decides to forego college. But for leftover funds, the money that would have gone to pay for college can be used to pay for future retirement expenses instead—and preserve its tax-free growth in the process.

Fewer Stocks, More Private Equity

It’s not generally known that the number of publicly-traded stocks has fallen substantially, from more than 8,000 in 1996 to roughly 3,700 today. Does that mean that there are fewer companies today than there were three decades ago?

Actually not. Today, a growing number of companies are staying private, often owned, in whole or in part, by private pools of investment capital known collectively as private equity (PE). By one estimate, PE funds owned approximately 26,000 companies at the end of 2022, the most recent figures available. And some of the PE firms that have been buying companies have become the largest employers in America. Carlyle, KKR Private Equity and the Blackstone Group are the third, fourth and fifth-largest employers in America, right behind Walmart and Amazon.

PE firms finance themselves by raising capital from investors, and then use the money buy out publicly-traded companies and take them private, or firms that have never gone public in the first place. The goal is to cut costs, strip out assets and then eventually sell for a profit, sometimes to another PE firm. This structure is not very different from the infamous trusts of the 1910s and 1920s, which operated outside of regulatory scrutiny similar to the way PE-owned private companies today are not regulated the way public companies are. That earlier experiment didn’t end well: there were well-publicized excesses, collapses, companies going out of business, bank runs and the Great Depression, among other things.

The PE firms are not just acquiring companies; a recent report found that three PE firms now own 11% of all the single-family homes for rent in Metro Atlanta—19,000 in all. The housing market in many American cities are adjusting to higher rents as for-profit firms buy up the available homes.

The trend has been to shift investment opportunities from what most investors are most familiar with—stocks—to blind pools managed by large firms who may not be long-term investors. Indeed the concern today is that PE firms are far more focused on maximizing short-term profits than they are at building the businesses they’ve acquired; on average, a PE firm expects to own a business for four to six years, and there have been reports that sound a lot like the corporate raider days of the 1980s, where firms were acquired, picked clean, and then abandoned into bankruptcy.

Another concern is leverage. Not all the money used to buy these firms is coming from investors; the funds have tended to borrow heavily to make their purchases, making them subject to collapse as interest rates rise and interest expenses become higher than the models predicted. Leverage can create oversized profits, but it can also come back to bite the over leveraged buyer.

What to make of all this? The first takeaway is that the stock market no longer represents the economy, and the disparity is increasing. But it’s also possible that the publicly-traded companies that most of us invest in will tend to have longer-term visions for their firms than the short-term-focused PE buyers, which means their longer-term prospects might be better. We won’t know how all this plays out for some years to come. But in the past, this same movie has not given investors—or the U.S. economy—a happy ending.

Sources:

- https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-consumer-prices-suffer-steepest-fall-since-2009-deflation-risks-stalk-2024-02-08/

- https://www.reuters.com/world/china/pressure-grows-china-big-policy-moves-fix-economy-2024-02-22/

- https://www.reuters.com/world/china/weak-data-limited-stimulus-keep-investors-away-china-2024-01-17/

- https://www.taxnotes.com

- https://www.bankrate.com/retirement/roll-over-529-roth-ira/

- https://www.cnn.com/2023/06/09/investing/premarket-stocks-trading/index.html

- https://www.theverge.com/23758492/private-equity-brendan-ballou-plunder-finance-doj

- https://news.gsu.edu/2024/02/26/researchers-find-three-companies-own-more-than-19000-rental-houses-in-metro-atlanta/

- https://content.clearygottlieb.com/pe-articles/private-equity-outlook-five-predictions-for-2024/index.html