Bankruptcy Epidemic

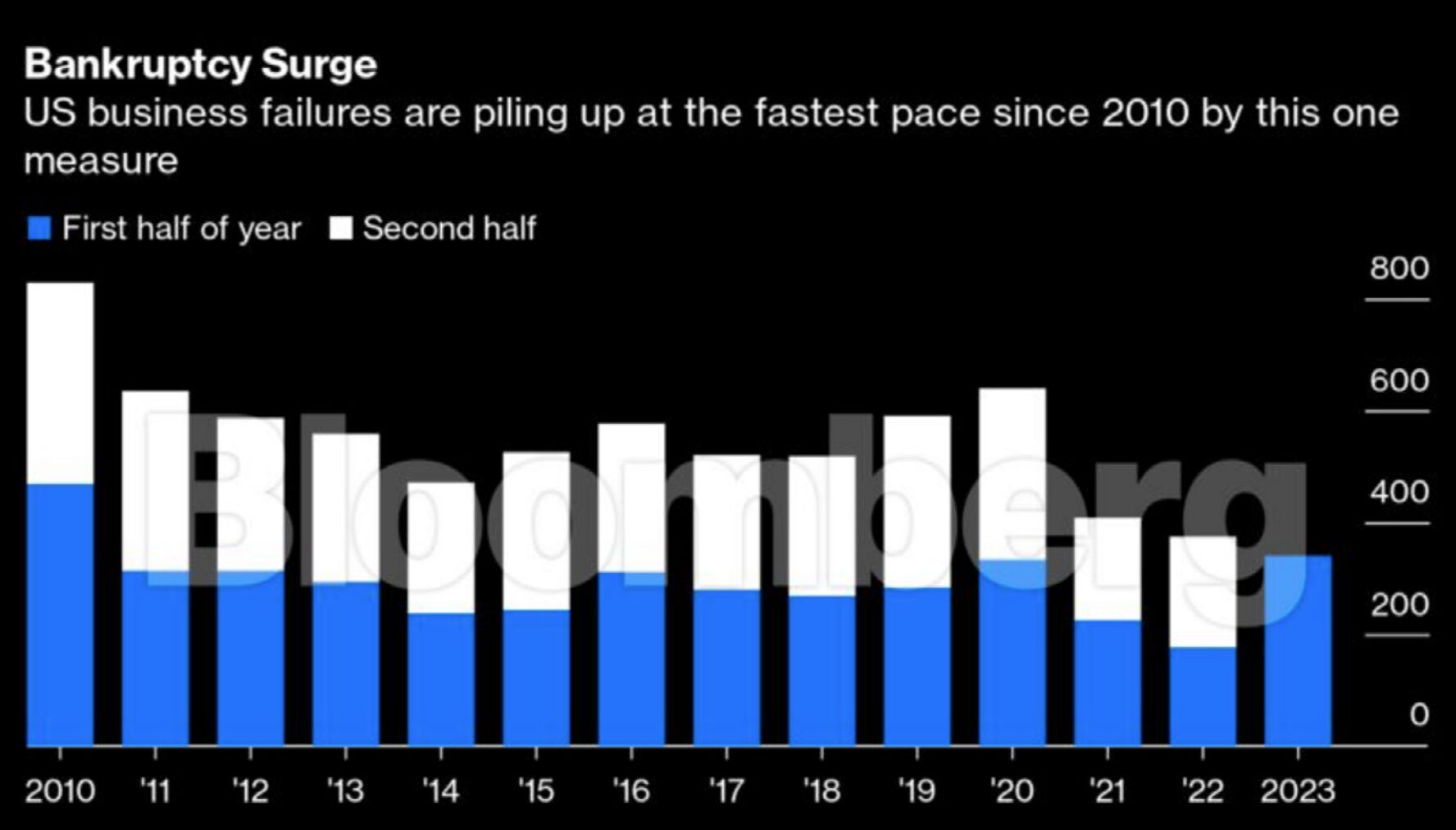

If you’re looking for something to worry about, consider bankruptcies. Normally, we see an uptick in companies filing for bankruptcy during recessions—for obvious reasons. An economic slowdown generally means fewer buyers spending less money, and companies that over-expanded, took on too much debt, or were poorly managed from a fiscal standpoint may be too weak to withstand the unexpected shock to their revenues and earnings. But right now we aren’t in a recession, and yet bankruptcies around the world are soaring. S&P Global Market Intelligence reports that in the first six months of this year, U.S. companies filed for bankruptcy protection at a rate not seen since 2010. In England and Wales, corporate insolvencies are near a 14-year high, Germany has seen its bankruptcy rate jump almost 50% over last year to the highest level since 2016, and Japan is experiencing a bankruptcy rate that is the highest in five years.

What’s going on? Even though labor markets and corporate profits overall are still at relatively high levels, there are other factors that are testing the resiliency of companies that got too far over their skis. Some firms over-leveraged themselves and were hit by the surge in interest rates. The aftershocks of high inflation were felt by companies that didn’t have a lot of pricing power, and were selling products at prices that became gradually unprofitable in order to protect market share.

So far, the bankruptcy wave hasn’t hit too many large corporations—the biggest example is US housewares giant Bed Bath & Beyond. But if the trend continues—and it might if we finally experience an economic recession—then the insolvencies could trigger a non-virtuous cycle of suppliers not getting paid, workers losing their jobs, banks further tightening their lending criteria—and more companies going bust. A number of boardroom executives are quietly crossing their fingers in hopes that interest rates will fall to more manageable levels; otherwise, a prolonged period of corporate distress could be in our future.

Buying International

In investing, the most normal inclination in the world is to question why an underperforming investment was included in the portfolio. Recently, those questions have surrounded international stocks, which, since January 2008, have consistently underperformed the U.S. S&P 500 index to the tune of 6.5 percentage points a year. Why not go ahead and ditch those foreign stocks and buy American?

A recent report in the Journal of Portfolio Management acknowledges that, in fact, international equities have actually underperformed U.S. large-cap stocks for the past 30 years. But looking back over longer time periods, and looking deeper, it found some interesting insights which might be relevant today. Looking deeper over the past three decades, the researchers noticed that foreign companies were not actually performing better, or growing faster, or becoming more profitable. Instead, investors were increasingly willing to pay more for U.S. stocks during that time period. Another way of saying that is that the valuations tripled, as measured by one common measure of price/earnings ratios.

Looking further back in history, the researchers noted that U.S. equities underperformed the EAFE (international stock) index in three of the past five decades: the 1970s, 1980s, and 2000s.

What does this mean for investors who are impatient with their international stock performance? It means that returns move in hard-to-predict cycles. International will sometimes outperform U.S. for long periods of time, and then (as has happened recently) the reverse happens—all of this unpredictably. It also means that U.S. stocks are pretty expensive right now; the Cyclically Adjusted PE Ratio is currently up around 30.1, well above the historical mean of 17. If investors decide that the earnings U.S. stocks are worth something closer to what they have paid historically, we could see a pullback in valuations—and those international allocations will become the future hero of investment portfolios.

But aren’t U.S. companies inherently superior to companies located in other countries? A whitepaper published by the U.S. Federal Reserve notes that the U.S. has experienced some unique tailwinds to its stock prices over the last 30 years. Both interest rates (meaning the cost of borrowing) and tax rates declined steadily over that period. As a result, profit growth exceeded the overall growth of the economy. But today, both interest rates and tax rates are likely to rebound, turning the tail winds into headwinds.

None of this suggests that we can actually know anything about what will happen tomorrow, or next year, or even the next several years. All we know is that buying or selling based on yesterday’s information seldom leads to great outcomes. Just ask investors who decided to go all-in on Japanese stocks in 1990, after Japanese stocks had experienced several decades of radical out performance. The subsequent returns have been dismal, and with the benefit of hindsight we can see that those investments were significantly overvalued.

Exploring the Digital Dollar

The U.S. Fed is experimenting with a digital dollar, but this does that mean embracing bitcoin?

The answer to the second question is: absolutely not. But the concept of a digital currency apparently intrigues the Federal Reserve Board and some of the largest members of the banking community. For the past 12 weeks, the Fed’s New York Innovation Center simulated a process of issuing digital money that represented actual customer deposits. It found that the digital dollars, sent and cleared through the blockchain technology behind bitcoin and a number of cryptocurrencies, were able to improve the speed and efficiency of payments without altering the legal treatment of the de-posits.

Participants in the experiment included giant banks Citigroup and Wells Fargo, who noted that the digital version of currency especially facilitated speed and efficiency when moving cash across borders. The test proved that converting actual investor deposits into their digital equivalent (and, of course, back again) didn’t break any U.S. laws or compromise the account ownership of banking customers.

Does that mean that we are about to move into an environment where all transactions are digital, or that the government will stop printing greenbacks? Conspiracy theorists are free to speculate, of course, but the most immediate impact of the experiment seems to be that banks and the Fed—and foreign firms collecting or paying dollars—may have found a speedier and more efficient way to transact business through the blockchain rather than the cumbersome systems that have been in place for de-cades. Fed officials were quick to say that there are no plans to create a digital dollar, now or in the future. The best speculation, if you want to indulge in it, is that the global bank-ing system would like to take the best features of bitcoin and its ilk and leave the wild price swings to the more adventurous crypto investors.

Sizable Cities

What are the largest cities in America? If you answered New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston etc., then you’re answering a different question. ‘Largest’ implies not population but land area, and the most expansive cities are seldom the most populous ones.

Take, for example, Sitka, Alaska, where 8,458 people—roughly the same population as a city block in New York City—occupy 2,870 square miles of land and 1,945 square miles of water area within the city limits. To put that into perspective, that’s more than twice the size of the state of Rhode Island, not far from the size of Connecticut.

Sitka is the largest city in America, closely followed by Alaska’s capital, Juneau, which encompasses 2,704 square miles of land and 550 square miles of water. Wrangell, AK (3,476 square miles of land and water) ranks third, followed by Anchorage, AK (1,946 square miles).

If you’re looking for the largest cities in the ‘lower 48,’ then Jacksonville, FL covers 874.5 square miles of land and water (a little over half the size of Rhode Island), followed by Tribune, KS, whose city lim-its include 778 square miles (none of it water). Among other major cities, Houston, TX (671 square miles), Oklahoma City, OK (620), Phoe-nix, AZ (519), San Antonio, TX (504) and Nashville, TN (497) are notable for their expansive boundaries. Los Angeles residents are spread out over 501 square miles.

Meanwhile, New York’s five boroughs and 8.8 million people are distributed over 300 square miles, and residents of Baltimore, MD (population 585,000) live on just 92 square miles. Seattle (83.9 square miles of land area), Des Moines, IA (88.2) and Milwaukee, WI (97) are among the least aggressive cities when it comes to annexing their surrounding territory.

Rates Moving Rates

The U.S. Federal Reserve Board once again raised the so-called fed funds rate, the rate that our central bank charges lending institutions on overnight loans. Does anybody care?

Most of the attention in the press centers around what this tells us about how the Fed economists and governors are thinking, and whether there will be more rate hikes, and what the impact will be (or not be) on the inflation rate and the prospects of a recession. As it turns out, this particular rate hike was relatively modest (a quarter of a percentage point, to 5.5%) and anticipated well in advance.

But there are more mundane impacts that the fed funds rate can have on those of us who live normal lives. Perhaps the most direct is a return on savings accounts and cash. Not long ago, before the Fed decided to attack inflation, people were earning around half a percent a year on their parked cash. Today, it’s possible to shop for certificates of deposit yielding 5%. There is no direct connection between the Fed actions and short-term interest rates, but they do tend to move in tandem.

Another impact is credit card debt. When the Fed raises rates, credit cards raise their rates accordingly. Auto loans and personal loans will charge higher interest rates, and most of us have watched mortgage rates move higher in loose lockstep with the Fed’s policy decisions.

The reason the U.S. central bank moves these rates up or down is directly tied to the behaviors it wants to influence. Right now, with these hikes, Fed economists think that this is a good time to encourage saving and discourage borrowing and leverage—basically cooling off the pace of the economy, and reducing the demand for goods and services that cause inflation to remain persistent.

And it’s not alone. The Euro-pean Central Bank also raised its equivalent rate by a quarter of a percent, as did the Bank of Canada earlier this month. Savers rejoice, borrowers despair.

Click the button below to download a version of this article.