Backdoor Loophole

Backdoor Loophole

Maybe this financial planning strategy is a loophole, and maybe it should be closed based on current tax policy. But the recent tax act, and several previous ones, failed to prevent people from making so-called ‘backdoor’ Roth IRA contributions.

The strategy is a workaround, around the fact that the IRS says that individuals with more than $153,000 in adjusted gross income, or couples earning over $228,000, are not permitted to contribute to a Roth IRA. Why would they want to? Unlike a traditional IRA, contributions to a Roth are not excluded from taxable income. (AKA after-tax contributions.) But the money contributed to a Roth, and all of the appreciation of its investments, can be taken out tax-free upon retirement. If you think taxes are going up, or you want more control over your taxable income during your retirement years, then a Roth account can be a handy part of your overall retirement assets.

So how does this ‘backdoor’ strategy work? Somebody whose income is above those thresholds can still contribute to a Roth account, under current rules (which have been threatened over and over again but are still perfectly legal) by first making a (nondeductible) contribution to a traditional IRA account. There are no income limits to who can make this contribution, which is limited to $6,500 a year (or, if your taxable income is lower, then your taxable income), with a $1,000 additional legal contribution for people 50 or older by the end of 2023.

Then you (or your advisor) would contact your IRA administrator to convert that contribution to a Roth IRA. That converts the contribution from tax-deductible to post-tax dollars, but it gets the money into an account that will never be taxed again.

The conversion can be a rollover from your traditional IRA into the Roth IRA, but a better strategy is a trustee-to-trustee transfer, where the traditional IRA provider would send the money directly to the Roth IRA provider (often the same entity).

Some individuals may benefit from a so-called ‘mega backdoor’ Roth contribution, which would generate higher contributions to the Roth account. This supersized version of the backdoor Roth works for individuals who have a 401(k) plan at work; an individual could put up to $43,500 of after-tax dollars into their plan, and up to $22,500 in deductible contributions, and then roll that money right back out into a Roth IRA or Roth 401(k).

This process can be complicated, so it helps to have a professional involved, and not all 401(k) plans permit the strategy. The plan has to permit in-service distributions while you’re still working at the company, or let you move money from the after-tax portion of your plan into a Roth 401(k) plan administered by the company. Additionally, not all 401(k) plans allow after-tax contributions.

For at least the past three years, there have been proposals in Congress to terminate these ‘backdoor’ strategies, and it’s logical to imagine that our elected representatives will eventually close this ‘loophole,’ but in the meantime feel free to enjoy the benefits of it while you can.

Bond rate Apples to Apples

You can be forgiven for scratching your head at the current bond market, and one of the more perplexing aspects of it is the yield curve in the municipal bond environment. According to Bloomberg, the current average yield on muni bonds with a 1-year maturity is 2.66%. But let’s say you want to take more risk and go out five years; what is your reward for taking that extra risk? It’s actually negative; the average yield on 5-year bonds is currently 2.19%.

Of course, ‘average’ covers a lot of territory, from low-rated to high-rated, across different states and municipalities, covering a lot of different projects and funds. And the other thing you have to consider is the tax-equivalent yield of the muni coupon vs. the more commonly-quoted corporate bonds.

The what? Most municipal bonds are not taxed at the federal level, and if you happen to live in the state where they are issued, you also escape state taxation on their yields. So you have to factor in the fact that these yields are tax-free in order to compare apples (the tax-equivalent yield of the muni) to apples (the after-tax yield of the corporate bond).

Fortunately, there’s an easy calculation engine on the web (go here: Tax-Equivalent Yield Calculator), where you enter the rate of return of the muni bond you’re considering, and your own marginal tax rate, and it will give you the yield that you can compare with a taxable bond. Let’s say you’re in the 32% tax bracket (for joint filers earning more than $340,100) and you buy that ‘average’ one-year muni bond at a 2.66% yield. Plug in the numbers and you see that the corporate bond would need to yield 3.91% to provide a superior after-tax return. But if you’re in the 22% marginal tax bracket (AGI above $83,550), then the corporate bond would only need to yield 3.41% to offer the same after-tax return.

Municipal bonds are not appropriate investments in a traditional or Roth IRA, where bond yields are not taxed each year regardless of what kind of instrument you purchased. But for taxable accounts, this calculation should be a consideration when you’re investing in fixed-income individual bonds, funds or ETFs.

Volatile Gas Prices

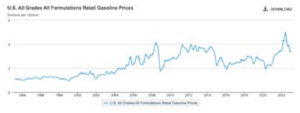

If you enjoy painful memories, then think back to when the average price of gasoline at the pump was up over $5.00—last June. Today, the average price around the country is around $3.50, and as you can see from the historical chart, that’s somewhat more expensive than what we were paying prior to 2008, but roughly average for the period since then. You can also see that the price since 2008 has been fairly volatile; the price line is much more jagged recently than it had been before.

The reason for the price instability is that it’s very hard for producers and futures speculators to estimate how much demand there will be for oil, generally, in the U.S. and global economy. The job of making these estimates, and betting on them, falls to traders in oil futures contracts, who may be investors, speculators or companies that simply want to lock in a price for their future energy needs. These traders look at whether supplies are diminishing, as when the war in Ukraine led to sanctions, or as Russia recently decided to dramatically cut back production. And they look at the projected demand, which may mean economic growth or decline (aka a recession). They look at inventory levels—that is, how much oil is stockpiled by various countries, and when the stockpiles dwindle, it takes away a dampening effect on the supply/demand equation.

The bottom line here is that the global supply and the global demand have become very finely tuned, so that small changes on either side can have outsized price ramifications—which means prices bouncing around as producers are trying to entice buyers, or as consumers are bidding for a resource that has become a bit more scarce. You can add to that the fact that the OPEC+ nations themselves make political decisions regarding how much oil to send to the markets; witness Saudi Arabia recently cutting production in order to raise the prices its oil could command.

Of course, despite the recent dip in prices, we Americans still complain about the price at the pump. But perhaps we should be more grateful. In Japan, a gallon of gas costs $4.71 on average. Australians are paying $4.37, Chinese consumers are paying $4.56, and in Spain you’d pay $6.61 a gallon to fill up your tank—and you’d be thankful that you’re not getting socked with $6.77 a gallon the way UK drivers are. And we should all express our sympathies to residents of Hong Kong, where gas prices are running a bit above $10 a gallon—the highest in the world.

The Declining Quality of Corporate Earnings

Corporate accounting and the earnings reports issued by publicly-traded companies (that is, those that trade on the stock market) would seem to be a matter of simple mathematics. The company took in X amount of money, its expenses in aggregate came to Y, and one might imagine that this tells us the earnings trajectory of the company (X today vs. X yesterday) and how profitable the company is (X-Y).

As it happens, accountants spend four years taking very challenging coursework that explores the many nuances of X-Y, and the surprising amount of subjective decision-making that goes into how companies can report their revenues and expenses. This matters because all of us read headlines saying that ‘corporate earnings are up,’ or that “ABC Company beat its estimates.” When you read that, or its opposite, you can be forgiven for imagining that the value of stocks are trending up or down.

The headlines today are talking about ‘solid earnings,’ which means growth above what was expected or above historical numbers. But corporate managers are under pressure to deliver good news about their companies in order to satisfy their shareholders and maintain their reputation in the marketplace, and they have lately been using their accounting creativity to dress up their balance sheets. Without getting into all the technical details of amortization and deprecation, carefully-timed write-offs and revenues booked before the payments are actually received, it appears that the managers have been working overtime to provide those positive headlines. A recent report by Bloomberg noted that companies, overall, reported 14% more income than cash flows in 2022 through September. For every dollar in reported profits, only 88 cents was matched by cash inflows—which the report says is the largest discrepancy since at least 1990.

The euphemistic term that analysts use is ‘poor quality of earnings,’ but you don’t see that phrase in the headlines because explaining it would require some depth of reporting and an understanding of all those things that accountants learn in college. Bloomberg cites ‘accruals’ (where companies have the leeway to book sales they haven’t been paid for yet) and counting inventory that is sitting unsold in warehouses as assets on the balance sheet. In one concrete example, homebuilder PulteGroup reported $2.6 billion in profits last year, but only took in $670 million of cash flows. The company had $2.3 billion worth of houses on its balance sheet that it had built but not sold.

Accounting tricks can only last so long before reality catches up to the balance sheet—and for some, it already has. Bloomberg reports that over the 12 months through January, 32% of the firms in the Russell 3000 Index fessed up to actually losing money, and such a widespread decline has happened only twice since 1978.

There is surely more to come. What all this means is that we should prepare for some bad news on corporate earnings at some undetermined point in the future, and not be surprised by it. Like all of us, companies go through rough patches and generally come out strong on the other side.

Rediscovering Budgeting

When millions of Americans leave work, they also leave behind the comforts of a paycheck. Suddenly, in retirement, they are exposed to a chore that they last experienced in their 20s and 30s—managing a budget that might feel tight. Chances are, it was not a pleasant experience back then, and they are not looking forward to it now.

The concept of budgeting has a limiting feel to it, with a dash of guilt mixed in. You are supposed to limit your expenditures below a threshold that may be set by outside influences (the press, so-called ‘experts’) and in extreme cases, you are told that your future financial success depends on giving up coffee in the morning or the now-famous frivolity: avocado toast.

In the past, there was the added hassle of tracking where your money went, but today there are a variety of tools that will do this for you, linking to your bank and credit card accounts and putting each expenditure into its proper category. Yes, you have to tweak the categories to customize them, but after that, you have the numbers part of it pretty much tamed.

The most recent approach to budgeting takes some of the guilt and much of the limit out of the process. You might have heard of the 50/30/20 framework, which is as simple as it sounds. The first 50% is allocated to your needs—that is, your basic expenditures like food, housing, transportation, etc. The next 30% is allocated to ‘wants’—things like dining out, travel, buying gifts. Under this formula, the last 20% is allocated to savings and debt repayment—but of course, retirees are generally not repaying their student loan debts and probably haven’t racked up unpaid credit card debt. Nevertheless, that 20% can become a kind of protection for various unplanned expenditures, like car repairs and potential healthcare expenses.

But retirees aren’t getting a regular paycheck, which means they have to calculate how much to apply that budget to. There are a variety of ways to calculate how much sustainable income can be derived from a retirement portfolio, some of them quite sophisticated, and all of them dependent on future assumptions that may or may not come true. One way to start is to tote up all the basic living expenses, and lock those down. Take Social Security, pension, or other stable income, and allocate that to the ‘needs’ bucket, and see how much of the needs are still uncovered. Those extra dollars become the amount that the retired couple would have to take out of the retirement portfolio simply to avoid sleeping under a bridge.

That’s the 50% part of the equation. Three-fifths of that amount would be, under the structure, available for spending on, well, anything the retiree wants. Does that size monthly expenditure feel comfortable, based on the total portfolio amount and time frame between now and the end of retirement? Is that a safe paycheck to take out of a portfolio that may be gradually depleted? This is a subjective decision, and of course, some of that 30% will be set aside for larger items, like a foreign vacation; it won’t all be spent in the same month.

There are no hard and fast answers to this question, but framing it this way might help a retiree get back into the budgeting game with an organized way of making spending decisions. They might be surprised to find that, unlike when they were in their 20s and 30s, budgeting can be uncomplicated and less painful.

What to Store With Your Estate Planning Documents

Keeping track of your estate planning documents and all the other items that you were told to keep in a safe place can be a daunting task. Even if you are the most organized person, keeping this up to date and knowing what to keep and what to toss can be a struggle. Most law firms will provide you with an estate planning binder, and this article will review what should be included in the binder from your attorney and what you should consider adding to make the job of your Successor Trustees a bit easier. Remember, you won’t be capable of helping the person when they are called upon to act, so you’ve got to be proactive here.

Free tip – maybe you are reading this, and you don’t have an attorney, nor an estate planning binder to organize. That is OK, keep reading because you may gain some knowledge that you can take to your own loved ones and help them out. If you are the person that will be tasked with dealing with their affairs when they are gone, you can help set yourself up for success by getting them organized now!

In your estate planning binder, you should have sections or tabs for your trust, pour-over will, power of attorney for finances, and health care documents. Those are pretty standard but keep reading because here is where you can take your estate plan from an average C grade to an A+.

- Real Estate: If you own real estate, it should be titled in the name of your trust. Place a copy of that deed transferring the property into your trust right there in the binder. This way your Successor Trustee knows you own that property and knows it was properly titled to your trust. This can be especially helpful if you have multiple pieces of property, and they are located in different geographical areas.

- Businesses: If you own a business or are a member or a shareholder of a company, it is important that your Successor Trustee knows this, knows what you own, and who to contact when you are gone. Consider adding the latest K-1, entity formation documents, and even the contact information of the management contact/company.

- Bank Accounts: It is helpful to know that you have accounts at Bank of America and Wells Fargo, but if you put a bank statement right there in the binder, now your Successor Trustee can see immediately how the account is titled, which branch you go to, and other pertinent information.

- Investment Accounts: Similar to bank accounts, but this should also show the contact information of your advisor, who will be super helpful when called upon to act.

- Retirement Accounts: Retirement accounts don’t get re-titled into the name of your trust, so here it is really important that you not only keep an account statement in the binder but print out and store a copy of the beneficiary designation form that you submitted to the institution (even better if you also include a confirmation of that beneficiary which your institution likely provided when you made that update).

- Memorial Instructions: I know it can be difficult to think about some of these end-of-life decisions, but the more information to provide to your loved ones, the less stress they will endure. Take the time to write down what you want to happen when you are gone.

- Personal Information: How much of your daily life is in your head? It is important to jot down the important information that your successors will need to take over and wind up your affairs. A good personal information worksheet will list your contact information, the contact information of your beneficiaries, your advisors, and other information that will be useful (think the combination of your safe).

Where to Store Your Plan: Important documents go in safe deposit boxes, right? Not always. If you store these documents in the safe deposit box then your successors will need to prove their ability to get into the box, and how will they do that? Well, the proof is in the box. Keep the plan in a safe place, and ensure your successors know where to find the binder that you just spent time improving, and how to contact your attorney.

Sources

- https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/investing/backdoor-roth-ira

- https://www.forbes.com/advisor/retirement/backdoor-roth-ira/

- https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/investing/mega-backdoor-roths-work

- https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/052715/muni-bonds-vs-taxable-bonds-andcds.asp

- https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/ratesbonds/government-bonds/us

- https://iqcalculators.com/calculator/tax-equivalent-yield-calculator/

- https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/PET_PRI_GND_DCUS_NUS_M.htm

- https://businesscouncilab.com/work/why-gas-prices-are-high-volatile-and-likely-to-remainthat-way/

- https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/gasoline_prices/

- https://www.advisorperspectives.com/articles/2023/03/01/corporate-americas-earnings-quality-is-the-worst-in-three-decades

- https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/finance/how-to-budget

- https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/finance/budget-worksheet

Author

Written by: Danielle P. Barger of Barger & Battiest Law, APC. Danielle P. Barger is a Certified Specialist in Estate Planning Trust and Probate Law (State Bar of California Board of Legal Specialization). For additional information on estate planning, please visit her website at dbsquaredlaw.com or call (858) 886-7000.

Click the button below to download a PDF version of this article.